Contextualizing Datasets: A Data Feminist Lens

Technica Hackathon, Research Track

1st Project, Completed: October 2020

Future: Ongoing :)

In October, I was selected to be a part of the Research Track at the Technica Hackathon for women/non-binary students, to work on the Contextualizing Datasets Through A Data Feminist Lens Project. And having bought the Data Feminism book (Catherine D'Ignazio, Lauren F. Klein) during its launch in March for my sister’s birthday, but ending up reading it on my own, attending its Zoom book talks and reading groups, and lurking on the Data + Feminism Lab website (hey, Harvard is really close to MIT!), I was so excited to be putting into practice the principles I was reading about.

Our project focused on the “Consider Context” principle of Data Feminism: aka, data is NEVER neutral. There are people at every step of the process: Who collects the data? Who is it being collected about? Who organizes the data, and how is it organized? What data is, or isn’t collected? Who analyzes it, who presents it? How do they present it? Who sees it? Who accesses the data? Who benefits from it use? These thoughts are encapsulated in a couple of my favorite questions from the book:

What power imbalances have led to silences/missing in data? What conflicts of interest prevent people from being transparent about data? How do we recuperate subjugated knowledge, and whose is it?

In other words, how does data hurt marginalized communities or other voices of less power — and how can we take back that power to include all writers in the narrative?

Data Feminism, by Catherine D’Ignazio & Lauren F. Klein, MIT Press.

early revelations

Going into this hackathon, I knew I wanted to use data related to body image or disordered eating, issues that disproportionately affect girls and women. And, surprise, surprise…

Barely any national health data includes sufficient information on disordered eating behavior. The most wide-scale survey, the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey, barely scratches the surface: it asks “How would you describe your weight?” (answers range from very underweight to very overweight), and “What are you doing about your weight?” (gain, lose, maintain, nothing much). And nothing, about warning signs of eating disorders or other restrictive behaviors: binge eating, extreme dieting, coldness, over-exercising, etc. A similar survey I found, titled Health Behaviour of School-Aged Children surveying youth across Europe and US/Canada, asked similar surface-level questions. And, this lack of data on an issue so important signifies the need for Data Feminism, to point out the holes in our so-called data-filled world. So what do I do next?

the process

With this initial discovery, I made a Top 4 datasets to work with:

Harmful practices and intimate partner violence - UNICEF DATA

Guttmacher Data Center (abortion / contraception)

2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (US based)

Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (2013-14)

When our group of about 8-10 students met on the day we had to begin research-hacking, I was the only one who brought forth datasets to use: and we split into 2 sub-groups based on the datasets, me spearheading the HBSC group! And it was quite a rocky journey — from dealing with unmotivated teammates, sifting through the enormous 200,000+ row dataset in Tableau, conducting qualitative research on HBSC itself, to waking up early just put all the last details together — shoutout to Rahat for being the one to stick with the project at the end! — all to figure out a way to tackle the question at hand:

How do we better contextualize and humanize data?

Here is what we found. Find an abridged version and video demos at our Devpost.

Contextualizing the HBSC Dataset

Introduction

The Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children organization is an international alliance of researchers that collaborates on a cross-national survey of school students in now ~50 countries (Europe, US, Canada) every four years. Starting amongst researchers from Finland, England, and Norway. Later developed by the World Health Organization’s Regional Office for Europe, it expanded research to countries and regions across Europe and North America, with those of a wide range of expertise: from epidemiology, psychology, to public policy.

Within the 2013-14 Survey Data, we are zooming in on body image and mental health-related aspects of the youth surveyed because of the growing prevalence of unhealthy body image and lowered self-esteem. In particular, we hope to better contextualize the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children data in its methods, collection, and usage with two goals: 1) so the youth the data describes, and those directly involved with their well-being, can better understand their own health, and 2) so we can realize the biased or missing narratives & pieces from this “holistic” overview of our youth, upon which important policies and lobbying interests are based.

The Other Principles of Data Feminism

By doing both qualitative research and data/imaginative visualization, we examine the context of HBSC data through the principles of Data Feminism.

1. Examine power:

First, there are clear imbalances and biases in the researcher pool and data processes. For outside researchers or educators who want to investigate HBSC further, a number of papers on the history methodology of HBSC must be purchased for use. As for national research teams, each is led by a Principal Investigator that must satisfy a number of requirements, including a Ph.D. Team members are mostly selected by the PI, and HBSC leadership, like the International Coordinator or the Data Bank Manager is elected internally.

One of the most surprising facts is that data is only available to non-HBSC researchers only after 3 years of finalization of the data: so, if non-profits, educators, or other parties want access to health data on youth, any information they can obtain would be outdated for any current solutions they want to build (this is also why we looked at the 2013-14 Data). And finally, requests for full survey protocols (describing reasoning behind questionnaire development, collection strategy as a whole) must be approved by HBSC: within 30 days, or perhaps more (I have yet to be approved). And to top this ice cream sundae — an International Report is written and released with key insights for each survey, but researchers are not allowed to publish their own findings before the IR is, and each paper has to be co-authored or receive consultation from a PI. While these rules may have been established for quality of work and security, the measures also create a funnel of what info is collected on children and how it is collected, and what they deem matters to investigations of youth physical, emotional, and social health. And with PIs and researchers likely to be dominated by older and well-educated, men: there can be crucial perspectives that we could be missing, from community leaders, to the youth themselves.

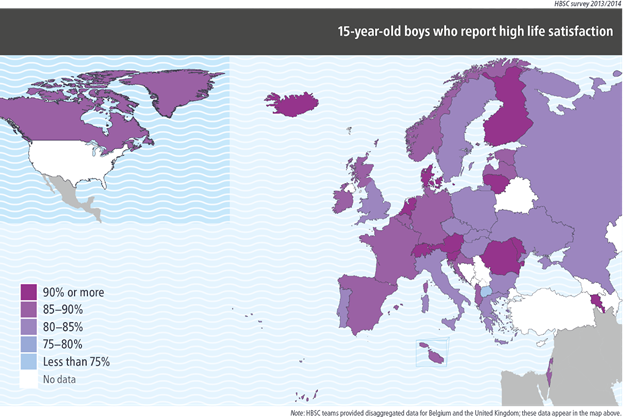

15-year-old boys who report high life satisfaction

from HBSC, 2013-14.

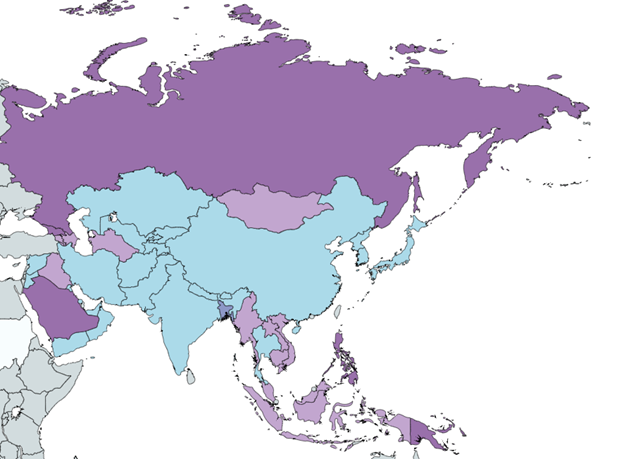

15-year-old boys who report high life satisfaction in Asia

generated from real data, by Rahat Choudhery.

2. Embrace pluralism:

The survey has expanded research to almost 50 countries and regions across Europe and North America, but HBSC network membership is restricted to Europe WHO Member Countries, US, and Canada, which doesn’t accurately reflect students of that age group in other countries. While we acknowledge HBSC has Western nations as its scope and that other nations are fully allowed to make Linked Projects with access to some of their research and networks, there are not as many resources to support them (especially smaller ones, that may need data to address very pressing problems). And, this establishment of a centralized, Western methodology of aggregate data on youth creates a Western “norm” on issues of today’s youth, when the fuller picture may be much more multi-faceted.

3. Elevate emotion & embodiment:

While there are questions that address emotional or social health, such as about bullying to feelings of trust or happiness at home/school, there is no way to further express student experiences beyond the number ratings, from the frequency of bullying to a number scale of happiness. And, teachers or schools don’t have ready access to anonymized data to help address certain issues or consider better school-wide solutions, and the numeric data itself cannot help students thoroughly convey nuances of their potential struggles. Moreover, the questionnaire itself asks general questions about satisfaction and happiness, but lacks in mental-health-oriented questions, such as those concerning eating disorder behaviors (binge-eating, restrictive eating or exercising), or early signs of depression, that should be essential to investigating youth well-being.

4. Rethink binaries & hierarchies:

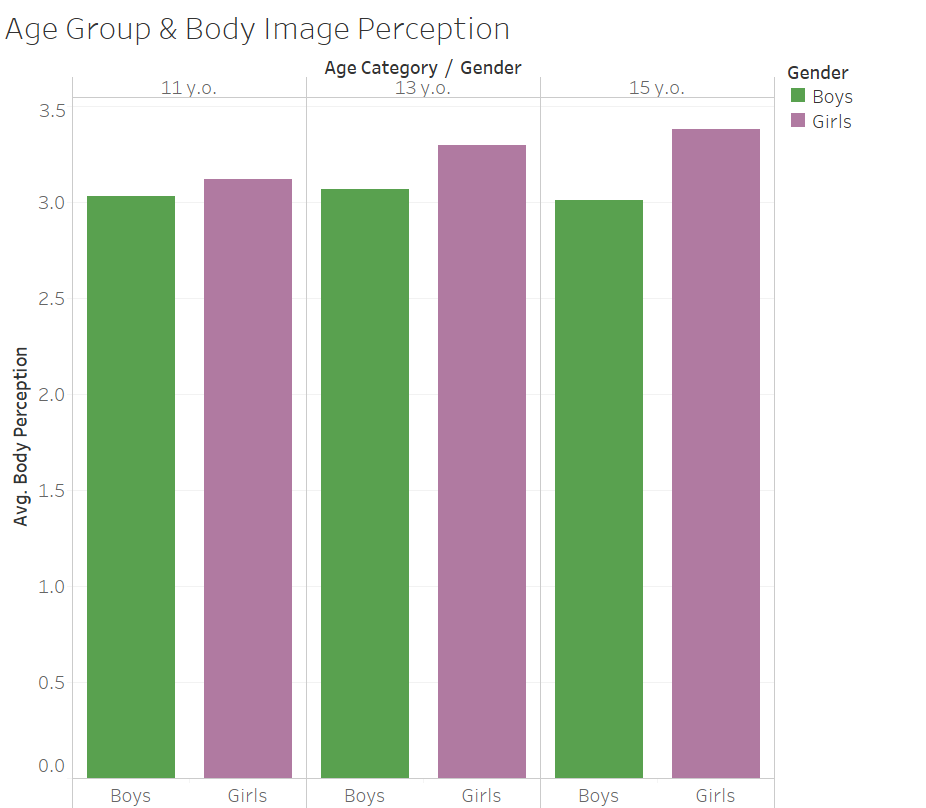

Age Group & Body Image Perception

Average of Body Perception for girls and boys in surveyed Age Categories. Body perception is ranked from 1-5 from 1) Much too thin, 2) A bit too thin, 3) About right, 4) A bit too fat, 5) Much too fat. Find more at hbsc.org.

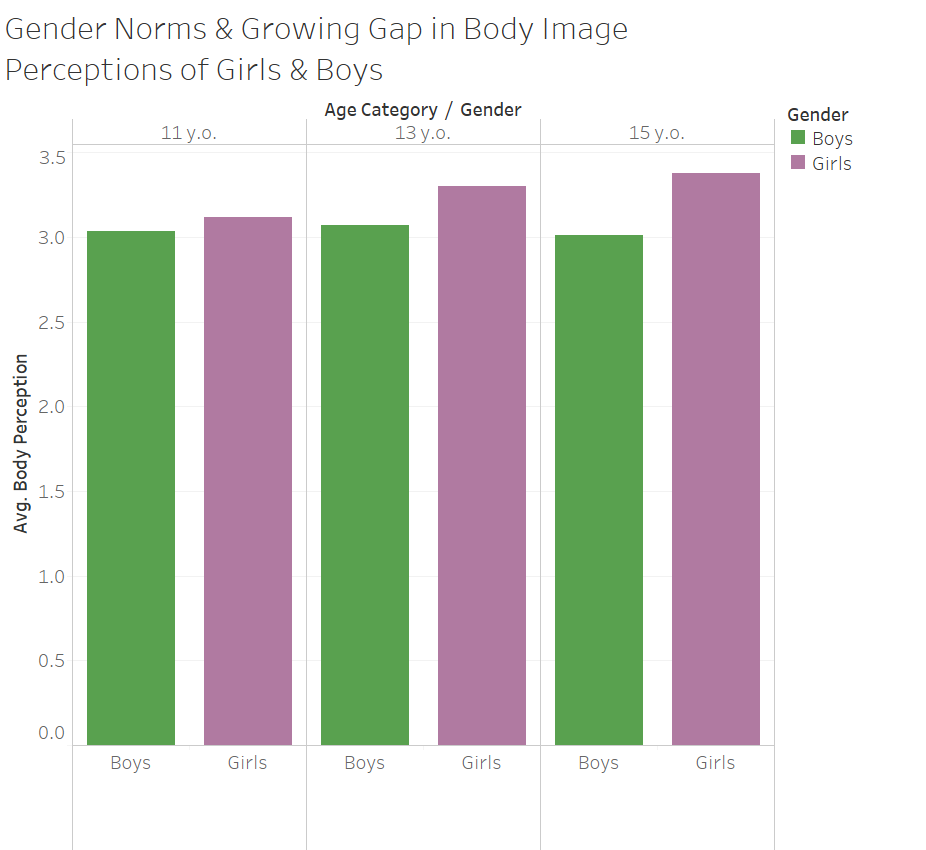

Gender Norms & Growing Gender Gap in Body Image

Average of Body Perception for girls and boys in surveyed Age Categories. Body perception is ranked from 1-5 from 1) Much too thin, 2) A bit too thin, 3) About right, 4) A bit too fat, 5) Much too fat. Girls' body image perception of themselves grow, the gap of self-perception widening with boys, likely related to weight stigma and beauty standards of gender norms. Find more at hbsc.org. We note that the survey's use of the gender binary as the norm excludes the experiences of those with other gender identities.

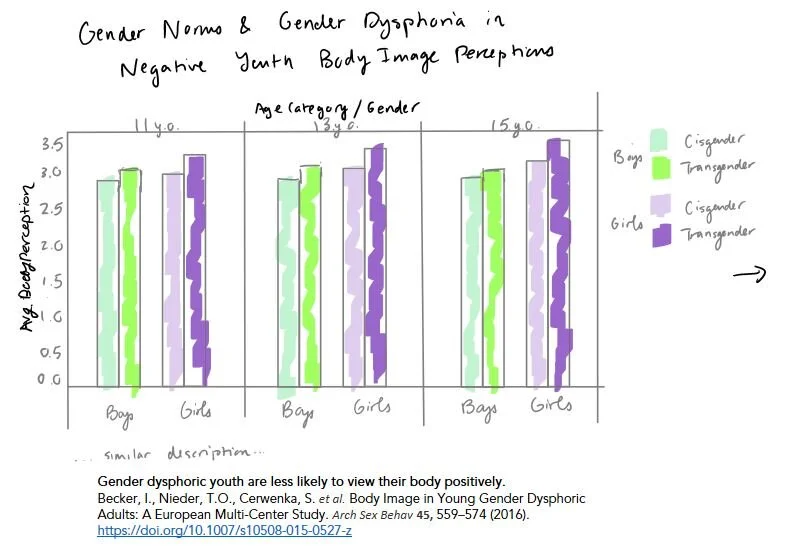

Gender Norms & Gender Dysphoria in Negative Youth Body Image Perceptions

By assuming the gender binary, the survey excludes the experiences of those with other gender identities, as well as the experience of transgender youth. An initial representation of the data would thus fail to acknowledge identities outside this binary. A better imagining would acknowledge this perhaps in the notes, and an even better reimagining would include these questions in the survey itself to acknowledge the diverse experiences, and address specific struggles of all youth: which, for instance, includes a increased likelihood in negative body image amongst youth with gender dysphoria.

Another note is the survey’s title, Health Behavior in School-Aged Children — which isn’t accurate. Data is, in fact, only collected from schools: and with how this data is used for research on public health policies or frameworks to improve upon youth health, any policy implications would leave out our most vulnerable children: those experiencing homelessness, poverty, or other struggles that leave them unable to even have a basic education.

5. Make labor visible:

Who was involved in taking data from the children, and are their efforts acknowledged in the report of HSBC? Answer: no, not really, since most surveys are administered by local schools and teachers. While it is unrealistic to acknowledge each school, let alone each teacher in such a large survey, this is a rather one-way funneling of data and power — from teachers (more likely to be women with less higher education and socioeconomic status) and local schools that interact day-to-day with these youth — to, university- or government-agency-recognized, PhD-educated, more older-male researchers and policymakers to decide on the large-scale directions and changes on youth health. So how do we tip the scales?

Now what? Challenge power!

What currently happens with the data?

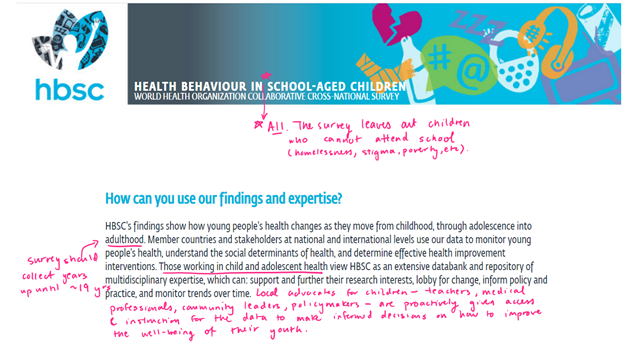

As noted on the HBSC website, “by sharing this information, stakeholders may gain insight and understanding about how the challenges of managing such an international research enterprise are met and how barriers to cooperation may be overcome. The ToR will also enable understanding of specific procedures of interest such as rules of publication and data access for those wishing to work with HBSC data.” So, as described before, this dataset is mainly used for HBSC-vetted, large-scale research conducted on multinational or national levels, without much incentive to give back this power of information to local communities and solutions.

What SHOULD be done?

We can now see the sore need for the last principle of Data Feminism: Challenge power. Here are a couple of ways to democratize this data so that more voices involved in the upbringing of youth in our communities are included in this conversation.

Make data & protocols freely available as soon as the information is finalized -- not after the three-year waiting period of a dataset release to be available to non-HBSC researchers.

Invite youth-involved community leaders (educators, counselors, etc.) to shape the development, administration and use of surveys, in schools as well as local organizations (shelters, community centers). Ask youth which aspects of their health they feel they need more attention on.

Set up frameworks that encourage or require HBSC researchers to help national or local education and government systems analyze and engage in data, and to consequently educate youth about their own current well-being.

Proactively provide local areas with data access and instruction to leverage data to make community-based decisions & solutions to improve youth well-being. Allow free & open access, or expedited processes for data access for educators and local leaders.

An annotation of their webpage — and what it should really say to distribute the power of data.

This survey is collected on 11-, 13-, and 15-year-olds in the HBSC member countries. And, I acknowledge that as a “graduated” youth, these suggestions may seem unrealistic and idealized, especially to be implemented on the scale of the World Health Organization. But if a small, national team of researchers is able to collect data on youth across their entire home country, I believe that they have the agency and capacity to set up channels to funnel their insights back to the youth and those who raise them. And, to acknowledge the labors associated with, and include in the conversation, those directly involved in the health of the literal futures of our countries. That is what we youth want, need, and sorely deserve.

but wait… i’m not done

So, reading Data Feminism and conducting this research, I was fascinated and frustrated by its revelations and explorations of the deeply-ingrained power imbalances within our data and technology systems. Moreover, the original question I wanted to tackle was body image & disordered eating, issues that are much more finely grained than whether you fit into the DSM-5 category of anorexia or bulimia or not — but an issue that lacks sufficient, centralized information. So where do I go from here?

After becoming passionate about the body-neutrality and anti-diet movement, I am gathering my own body of research based on my readings about the racism and patriarchy rooted in “obesity epidemic” and the toxic “wellness” movement (an abridged version!) With this at hand, I am planning to design a UI/UX project called Bodi: a community and educational platform for the anti-diet / Healthy At Every Size movement.

After discussing with a friend the arbitrariness of women’s clothing sizes that really affects our self-image — but the strange lack of data on this topic — I’m compiling a dataset of different brands, and “all” their measurements for women’s clothing. A crowdsourcing tool is to come. :)

And, I discovered:

The STRIPED Incubator at Harvard’s School of Public Health realized the same shortcoming that I did.

At STRIPED (Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders), their CDC Eating Disorders Health Monitoring Project has been fighting for what I also realized to be a crucial MISSING part of our national health surveys. “STRIPED successfully advocated for the inclusion of language within the spending bill requesting that CDC include disordered eating behavior questions within their youth and adult health surveillance system surveys. This language officially passed the House on July 31 and will be considered by the Senate later this year.” How crazy & awesome is that?! I’m definitely following the progress on this project, and hope to take some of these graduate-level classes, or incorporate my design, data, and/or coding skills into research opportunities at Harvard.

At the end of this all, I am proud of the HBSC investigation we did, but am even more excited about the conversation it has started within myself, with my peers, with our project mentors, and (metaphorically) the authors of Data Feminism. As someone who loves to write and who loves to hear people’s stories, it was empowering to hear Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein’s call to arms to not only humanize data, but to see the people beyond the data, and allow people — all of us — to have autonomy over the data, the bits of ourselves that represent us in the world.

TLDR: We should all be Data Feminists.

Credits:

Project outline, analysis and writing, Tableau & hand-drawn visualizations (Vanessa Hu)

Intro notes, map & pluralism principle; presentation partner (Rahat Choudhery)

Make labor visible: notes (Kerin Pithawala)